Eyes Wide Open

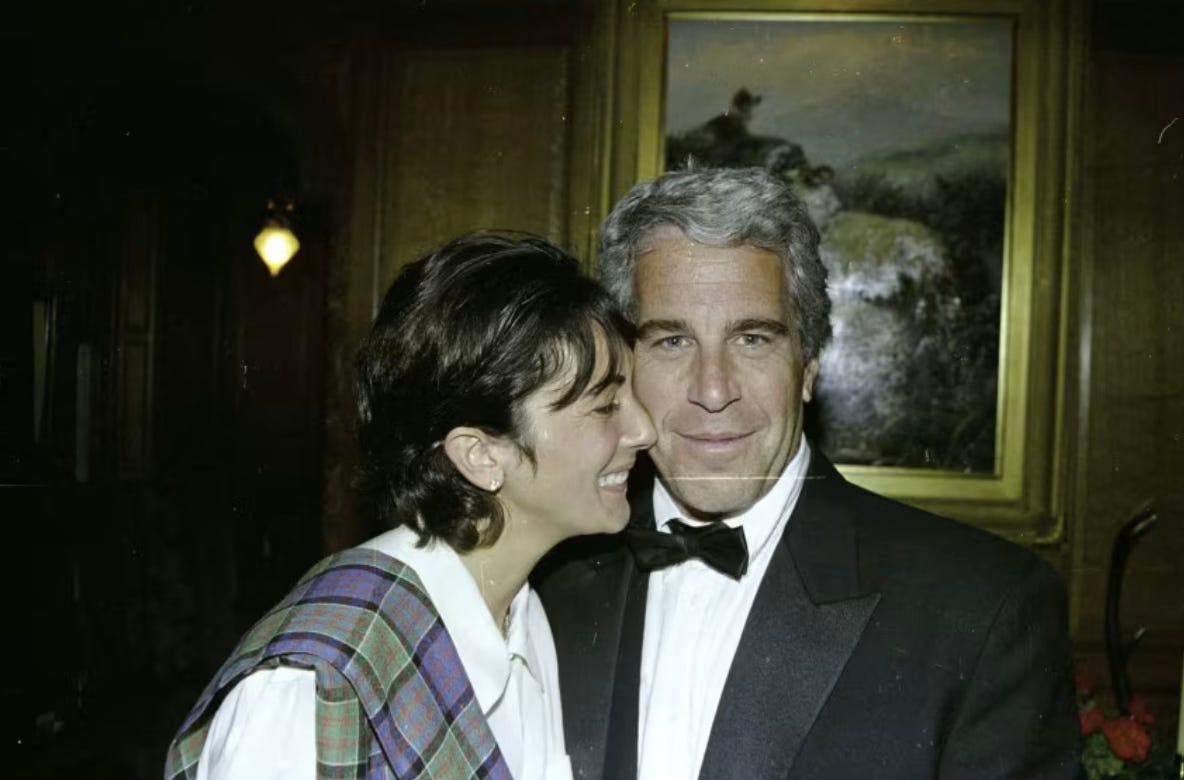

The Occult World Of Jeffrey Epstein

There is something about the Epstein story that refuses to settle. Even when the facts are laid out, the explanations feel thin. People sense that what was revealed wasn’t just crime, but a structure that doesn’t belong to ordinary moral life.

This isn’t an exposé or a conspiracy theory. It’s an attempt to describe what power looks like once it slips free of ordinary limits.

“Be suspicious of people who have, or crave power. Never ever go near power.

Don’t become friends with anyone who has real power. It’s dangerous.”

— Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick did not make Eyes Wide Shut to suggest that the powerful secretly dress in ceremonial robes or worship gods in hidden chambers. What he depicts instead is the emergence of a distinct moral sphere produced by extreme power, one in which exemption from ordinary consequence is assumed. In Kubrick’s rendering, the masked ceremony at the centre of the film is not erotic pageantry. It represents a domain in which ordinary rules no longer apply, identity becomes fluid, and consequences do not return to those at the top of the hierarchy. Eyes Wide Shut does not advance a conspiracy thesis. It identifies a recurring structural pattern in which power bends social reality until it answers only to itself.

Kubrick maintained distance from this logic in his own life. He withdrew from Hollywood, declined publicity tours, and avoided celebrity social circles. This withdrawal was not motivated by fear of elites as individuals, but by an understanding that proximity to concentrated power alters the conditions of perception. Such proximity reshapes what can be seen, what can be articulated, and what can be risked. Kubrick’s warning is therefore not moralistic, but diagnostic. Power constitutes a distinct order of being, and effective power tends to operate through concealment rather than visibility.

This is the correct way to approach the Jeffrey Epstein saga.

People often ask why Epstein behaved as he did, as though some secret code or private pathology must explain it. Such explanations are unnecessary. Extreme wealth alone is sufficient to reshape how an individual experiences the world. When a person possesses more money than could be spent across multiple lifetimes, money ceases to function as a form of scarcity and instead becomes an ambient condition through which reality is mediated. Constraints that regulate most human behaviour, including risk, exposure, accountability, and social sanction, lose their regulating force. At this stage, behaviour is no longer moderated by consequence but by access, namely access to people, places, narrative control, and institutional protection. In this way, unlimited resources translate directly into expanded latitude of action.

At this point, the occult frame becomes not merely metaphorical but structurally precise. The term occult refers to that which is hidden, set apart, or removed from ordinary social visibility. Epstein’s world required neither incantations nor deities in order to function as occult. It operated as a closed system governed by enclosure, initiation, and exemption. Those within this environment were not simply participants in wrongdoing. They crossed experiential thresholds that rendered silence more adaptive than exposure. In anthropological terms, this constitutes ritual, understood as a patterned transformation of status within a sealed social space. This structure aligns closely with the classical Hermetic systems, which organise power around separation, restricted access, and the containment of knowledge within bounded domains.

Many dominant narratives fail here. They assume that when wrongdoing becomes visible, individuals will refuse to participate. This misreads both incentive structures and human psychology. Journalist Michael Tracey has explored this failure in relation to Epstein and the broader dynamics by which narratives form around powerful figures. Across his commentary, he has shown how much of what circulates as “Epstein mythology” emerges less from evidentiary rigor than from institutional incentives: sensationalism rewarded, inconvenient facts sidelined, reputations protected. Journalists, politicians, and commentators rationalise their engagement according to career incentives and audience capture rather than sustained scrutiny

At a deeper level, this exposes a more general pattern. Individuals and institutions routinely accept money, access, or proximity to powerful figures even when they privately recognise impropriety. This is not naïveté. It is rationalisation under pressure. Participants tell themselves the resources will be used for good, that responsibility is diffuse, that refusal would only pass the opportunity to someone else. These are not moral failures so much as adaptations to a warped incentive field. Concentrated power generates pressures that shape behaviour across entire networks, extending well beyond any inner circle.

Once enough participants internalise these pressures, silence stops appearing exceptional and stabilises as the normal operating condition.

This is how an occult structure maintains itself: not through witchcraft, but through the distributed consent of those who benefit, fear exclusion, or calculate quietly that participation is safer than opposition. It is a social contract of geometric asymmetry, where the few at the centre extract protection, privilege, or exemption, while the many on the margins tolerate the arrangement because confrontation feels too costly, too risky, or simply pointless.

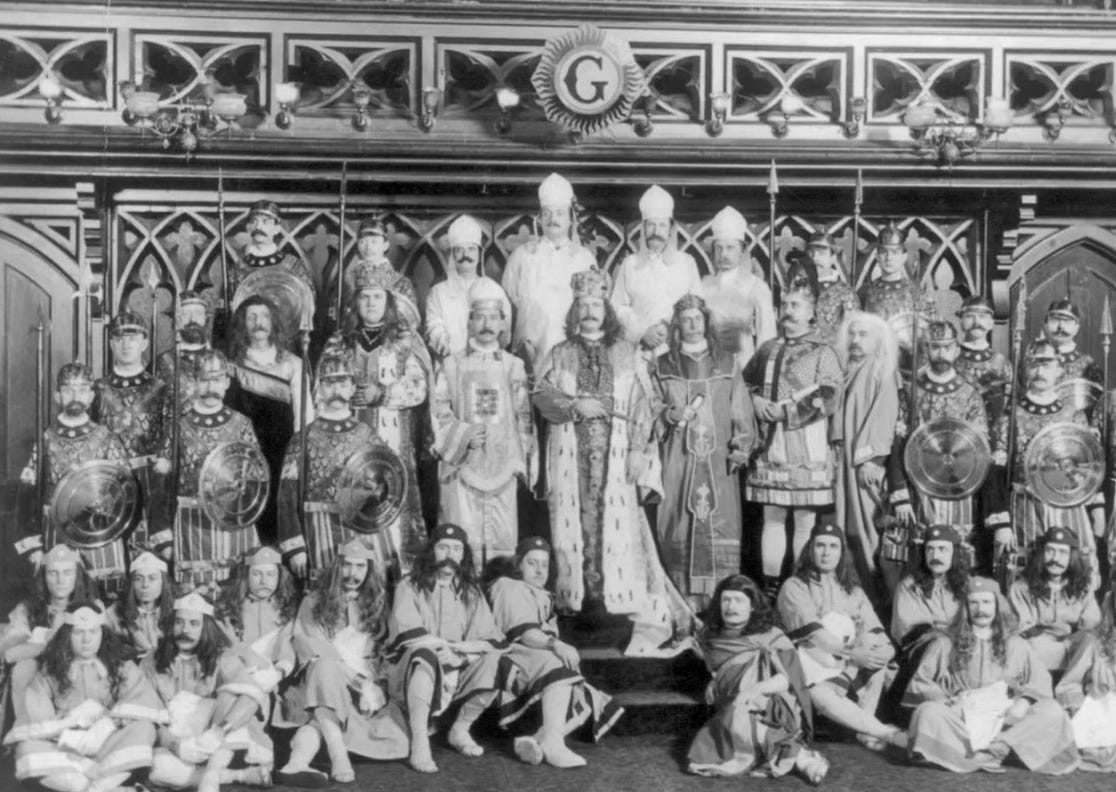

This pattern is not novel. Secret societies and esoteric organisations have operated according to similar principles for centuries. From the Eleusinian Mysteries to medieval guild structures and later fraternal orders such as Freemasonry, the underlying architecture remains consistent. These systems are characterised by graded initiation, selective disclosure, enforced silence, and the implicit or explicit promise that membership confers insulation from ordinary social rules. Knowledge is never disclosed in its entirety at once. Identity is reshaped incrementally, and each threshold crossed increases the cost of withdrawal, rendering compliance progressively more rational than refusal.

What matters in these systems is not belief, but structure. Initiation binds through experience rather than ideology. Oaths formalise silence, but shame and status do most of the work. Over time, secrecy becomes less a rule than a reflex. These organisations survived not because they were omnipotent, but because they made themselves indispensable to those inside and opaque to those outside. The cost of exposure was always higher than the reward.

Epstein’s world does not resemble a cult because it borrowed from ancient traditions. It resembles them because it obeyed the same underlying laws. Initiation, insulation, silence, and asymmetry are how power learns to endure.

Over time, such structures do more than organise people. They organise space. Secrecy requires geography. Initiation requires thresholds that can be crossed but not easily reversed. Enduring esoteric orders converge on the same principle: separation must become material. A bounded location becomes necessary, one in which normative rules shift upon entry and ordinary oversight loses its reach.

The island that constituted Epstein’s domain is symbolically significant for precisely this reason. An island materialises separation. Alternative rules prevail. Exit is constrained. Jurisdiction weakens. Once space is removed from shared governance, activity within it is regulated by internal logic rather than external accountability. This mirrors the historical function of temples, which operated as liminal zones set apart from everyday life.

Once space is set apart in this way, symbolism accumulates whether anyone intends it or not. Separation generates meaning. An enclosed place becomes charged simply by being unreachable. This is how temples, underworlds, and initiation chambers have always emerged. Not because myths were consciously invented, but because power, once insulated, begins to express itself symbolically.

Across ancient cultures, the sacred was rarely placed at the centre of communal life. It was pushed underground, into caves, crypts, inner chambers, or remote sanctuaries. The underworld was not imagined as evil. It was anterior, older than law, older than speech, older than permission. Entry marked a threshold. Ordinary identity loosened. Something irreversible was understood to occur. These were not places for casual visitation. They altered those who entered them, or refused to let them return unchanged.

That structure persists long after belief fades.

An island reproduces the same conditions. Time behaves differently. Memory shifts. The outside world grows abstract. What happens inside becomes self-contained. Silence becomes easier than explanation. Staying feels safer than leaving.

The abyss here is not a literal void beneath the earth, but a structural condition. It opens wherever accountability weakens. It is the gap between action and consequence. Within that gap, acts become possible that would be unthinkable under ordinary visibility. The abyss does not require belief. Neglect is enough.

This is why rumour and myth gather around places like Epstein’s island. Observers sense something has fallen outside the shared moral order. They reach for older language because modern categories fail. Crime feels procedural. Corruption feels insufficient. Neither captures how reality itself bends once it leaves common oversight.

The so-called temple structure on the island belongs here, not as evidence of belief, but as the crystallisation of atmosphere. Architecture does not need ritual to work ritually. Enclosure, elevation, symmetry, separation. These forms condition behaviour before a word is spoken. They announce exception. They signal that judgement does not flow outward.

Historically, the inner chamber was always the most protected space. Not because it housed gods, but because it housed exemption. Modern power reproduces this instinctively. It builds inward, not upward. It conceals rather than declares. It prefers depth to spectacle.

Once power is sufficiently insulated from consequence, it no longer needs mythology. Endurance alone confers sacral weight.

Kubrick understood this. Power does not simply corrupt behaviour. It reorganises reality. And real power hides, because visibility is the first constraint it ever accepts.

This was never really about sex. Sex was a medium, a way of testing boundaries and enforcing silence. It was never simply about money. Money was the solvent that dissolved limits and made consequences negotiable. It was never only about blackmail. Blackmail was leverage.

The power was the point.

The ability to act without consequence. To survive exposure. To exist beyond the shared moral field. Epstein was not an aberration so much as a demonstration of what power becomes when it is allowed to seal itself off from accountability, and of how easily the modern world learns to tolerate that seal, so long as it remains out of sight.

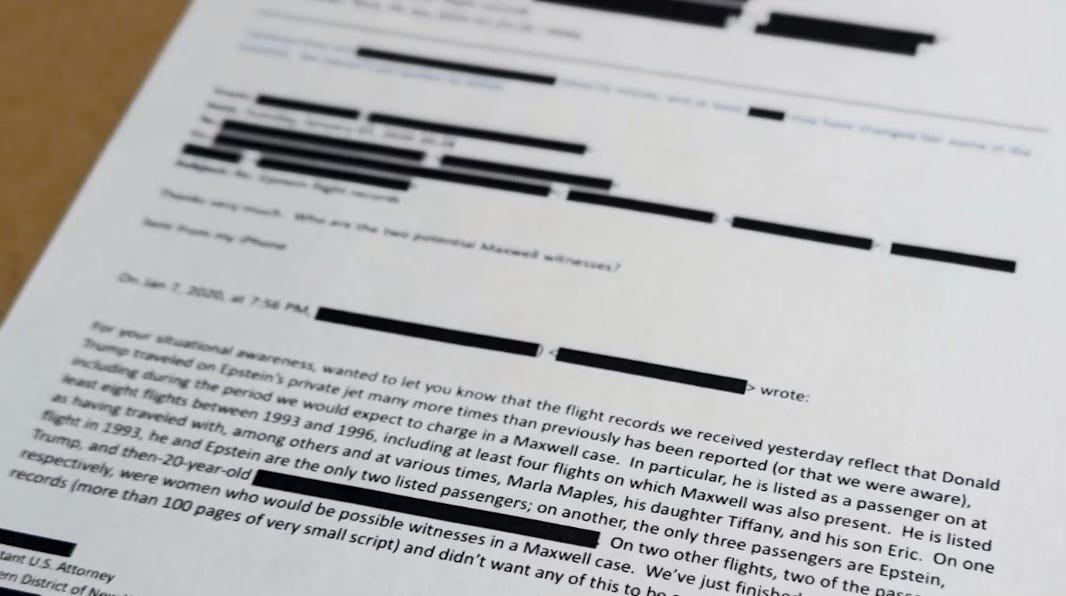

And now, much of this no longer sits out of sight. Files surface. Images circulate. Names recur. Connections repeat themselves often enough to stop looking accidental. What depended on distance is forced into proximity. It becomes clear how many were tied into the same web, through money, silence, favour, deference, or the decision to look away.

This is what exposure does. It doesn’t just reveal facts. It changes the field. The spell only works while it remains unexamined. Once the structure is dragged into the open, its power drains quickly. What felt vast and inevitable begins to look narrow and fragile. What once appeared sacral starts to resemble stagecraft.

This is the fate of all occult power when it is properly seen. The mystery collapses. The initiation loses its force.

Magic depends on distance, silence, and awe. Take those away and it has nothing left to work with. What remains is not revelation, but banality.

Systems of protection that only ever functioned because they were allowed to.

Power hates this moment. Because once it is exposed, it no longer feels inevitable. And once inevitability is gone, the structure that sustained it begins, quietly, to fail.

What comes next is never pretty. The emperor has no clothes, and once that’s obvious, the instinct is to blame, deflect, and fragment. But what’s really exposed is not individual guilt so much as structural sameness. The elites are not exceptions to the system. They are its repeatable parts. And once that pattern is visible, the protection it relied on weakens. Exposure rarely ends cleanly, and it rarely ends where it begins.

There is an old phrase, often attributed to the Illuminati, that is usually misunderstood. It was never a celebration of freedom. It was a description of what power looks like once it slips free of constraint.

Nothing is true. Everything is permitted.