The Chad Philosopher

Meet the womanizing, chain-smoking, philosophical legend who revolutionized ethics and then faded into obscurity

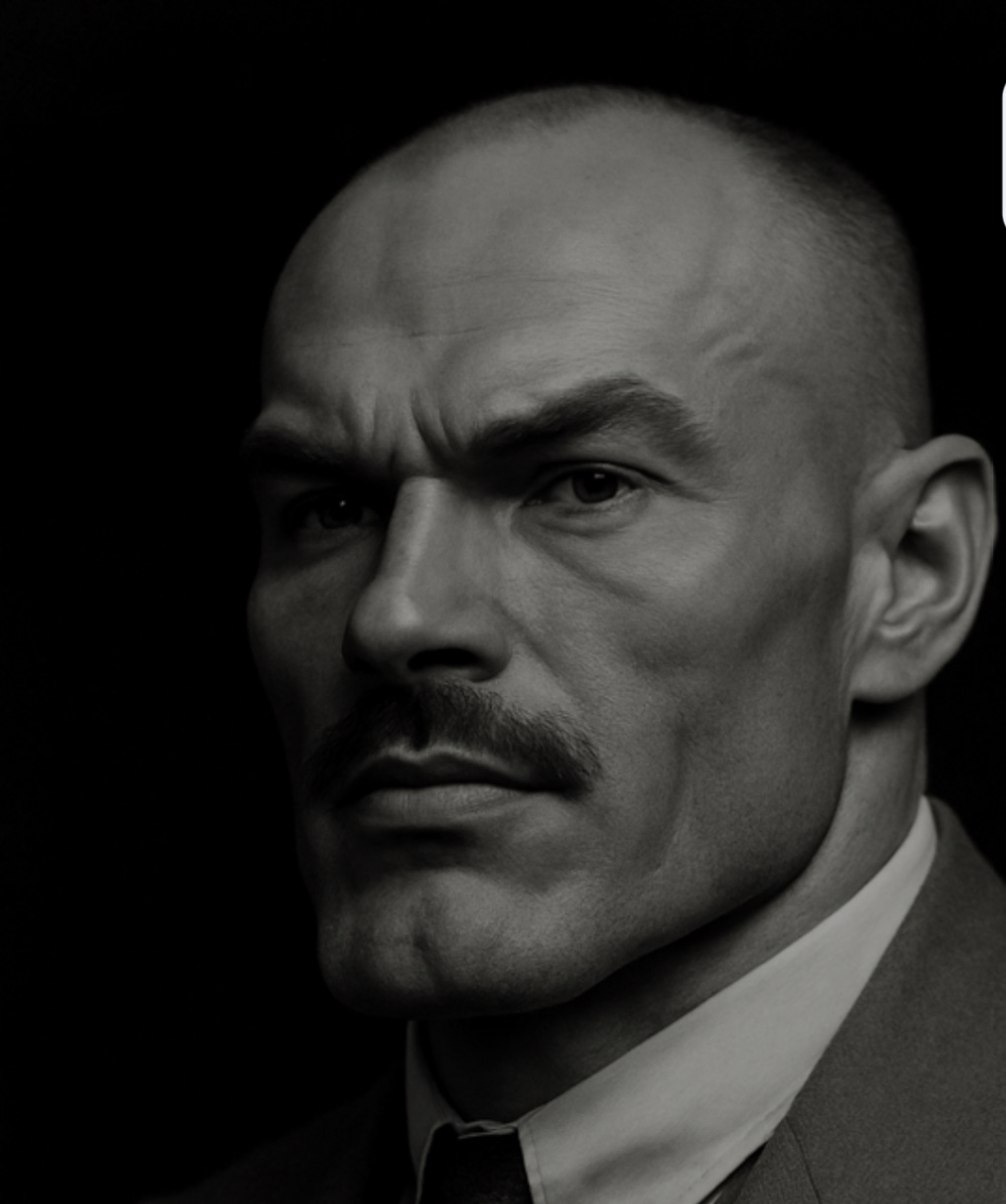

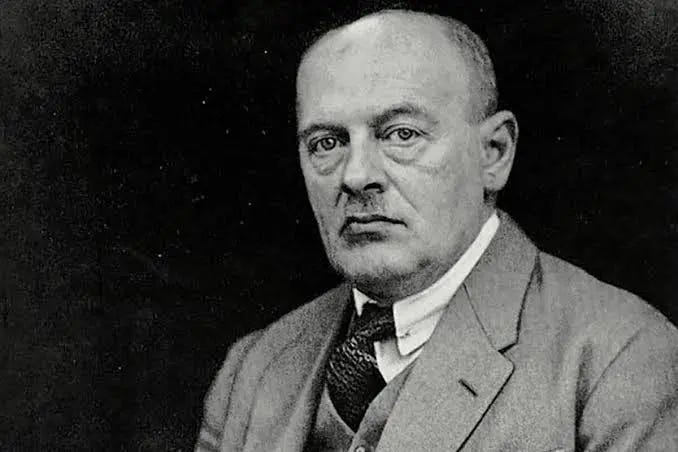

A few weeks ago I posted this article on Otto Weininger, where I dubbed him the “incel philosopher.” The article was well-received, and it got me thinking about whether there might be a “chad philosopher” as well. People can tell me who they think deserves this moniker in the comments, but once I considered Max Scheler, there really was no other choice. Scheler isn’t widely read today (at least in the English-speaking world), so this article will serve as an introduction to him and his thought as well as an argument for his status as a chad—perhaps as the chad—among philosophers. I’ll cover three things here: his life, his approach and his overall philosophical outlook. I will not, however, attempt to define what “chad” means here.

Fast Living and Faster Thinking

The words “philosopher” and “chad” are seldom used together. If anything, your average philosopher today is a nerd, a “bugman,” a neurotic—and it has been this way for some time. But there are exceptions to every rule, and today I am going to introduce you to a glorious exception: Maximus Scheler.1

First off, he was a wild man.

A lot of people preach about “dyonisian” living, but how many really expend themselves in interesting ways? People of that kind party till the early morning, snort lines of ketamine and waste their lives away in dead-end jobs. Scheler fucked everything that moved, smoked three packs of cigarettes a day, and wrote treatises on the most advanced philosophical problems known to man—in various fields, respectively. He revolutionized ethics, was the main intellectual influence of Pope Saint John Paul II, and during his funeral was dubbed by Heidegger as the “most powerful philosophical force in Europe.”

His life was unstable, exciting and tragic—marked by great highs and lows. I do not intend to offer a long biographical sketch here, so I will restrict myself to listing a few representative facts about Scheler’s life:

At 23 became involved with a woman 8 years his senior who was already married and had a kid.

He married her, then cheated on her a bunch,2 which drove her crazy and derailed his career.

He was fired from his position in Munich after a newspaper article claimed he had cheated (he sued for libel, lost).

He left his first wife for a younger, prettier second wife.

He lectured in bars and coffee houses, worked as a freelance journalist and culture critic.

He lost the opportunity to run a private magazine run by a rich benefactor because he refused to advertise Dresden china next to his articles.

He left his second wife for a younger, prettier third wife.

He wrote a letter to second wife on the eve of his honeymoon with the third, telling her that he still loved her and that he would see her when he got back.

He told a Catholic bishop who reproached him for his lifestyle that “I am the sign that points the way, but it doesn’t mean I have to go that way.”

He smoked 60-80 cigarettes a day and died at 53.

The overarching picture his life paints is that of a talented maniac, one with a special weakness for women. As his biographer writes, “throughout his life whenever he had to choose between his devotion to a transcendent God and the warm body of woman, with pangs of conscious but unable to do otherwise, he chose the woman.” (Staude, 6)

He was also extremely charismatic. His essays may be good, but he managed to pack lecture halls during his talks about metaphysics and politics. Some have even supposed that Husserl’s issues with Scheler were not the result of any intellectual disagreements (though there were many) but simple jealousy, because students preferred to listen to Scheler over Husserl.3

But all this is only a part of what makes him a chad: in real life he simply was a fast-living, charismatic stud. I don’t know many other philosophers about whom we can say that.4

Ironically, this heavy sensuality was offset by an equally strong religious instinct, and Scheler devotes many pages to speculative metaphysical and religious questions. During his time he was even known as the “Catholic Nietzsche,” until he abandoned Catholicism in favour of his own version of “panentheism,” wherein the human being acts as a kind co-creator of God.

As a Writer

Scheler’s status as the chad philosopher is by no means secured by his tumultuous personal life. If anything, it is his work which marks him out in this respect. But rather than try to distill his ideas into a simple, digestible summary—something which is impossible given the scope of what he wrote (he is one of those philosophers in whose work you can find everything)—I will present something much more modest: my own general impression of him.

Scheler’s essays are marked by a most unique combination of traits: on the one hand, he appears to be supremely well-read, effortlessly referencing everything from the Pre-Socratics to the latest discoveries in physics; on the other, he is a creative powerhouse with an almost super-human ability to make subtle distinctions. He is often thought of as a weird kind of continental philosopher: someone who writes crazy stuff in an analytic style.

The topics themselves are incredibly broad in scope. One finds his big books on ethics (Formalism) and religion (On the Eternal in Man), longish studies on specific emotions (love, shame, repentance, ressentiment), a book on sociology, another on the meaning of work and the metaphysics of perception, and articles on whatever random topic he may have been interested in.5 The commentators make a big point about his study of the emotional life, but he is really one of the last great polymaths that Europe produced.

This is not to say Scheler is easy reading, or that he is without his flaws. In fact, his unpopularity is in part a result of his difficulty—but this needs to be qualified. Scheler is not difficult because he uses language in odd ways (he invents words, but these are usually well-defined and not too difficult to grasp). Nor is he difficult because his thought is mired in abstraction. He is difficult for the simple reason that he expects you to know as much as he does. This means that he references philosophers in an off-hand way (especially Kant, Aristotle, Schopenhauer, and the thinkers from his own time) with the expectation that you know what he is talking about. It also means that he references himself all the time, with the expectation that you have read all his books.6

He is also a poor stylist. Much of what he wrote also seems to have been written in a single go, as first drafts, which means his thoughts are not expressed as succinctly as they could be. The ideas themselves are clear; his presentation, however, is often less so. He is also very bad at editing. When Husserl compiled his yearbooks, which were a kind of greatest hits from the early phenomenologists, the editor, Pfänder (another neglected gem of a thinker) had a fit about the number of errors in Scheler’s manuscript.

But—if' you’ll permit me to use the term “chad” as an adjective—there is something vaguely chad about this as well. To sit down and write an essay in a single go, to have perfect faith in yourself, to ignore the imperatives for brevity and succinctness, to include random paragraphs about the philosophy of poetry in an essay on the perception of other minds—all this reveals tremendous confidence and vitality. This method led to many breakthroughs; it also led to some rather silly mistakes and to many, many footnotes portending articles and books that were never published. But this too is part of his charm, I think. Most people try very hard to make their meager thoughts appear more impressive, but Scheler gives the air of someone who always knows more than he writes. He is an intellectual billionaire, and he writes with unsurpassed prodigality.

Those interested in writing would probably be best served by beginning with the Selected Essays, specifically Phenomenology of Cognition and A Theory of Three Facts, in order to get acquainted with his brand of phenomenology. After that, it’s probably best to brush up on Kant’s ethics and tackle Formalism, which is about as rich a book as one can find. But the patient reader can find interesting ideas on almost anything within his corpus, and you’re probably best off following your own interests.

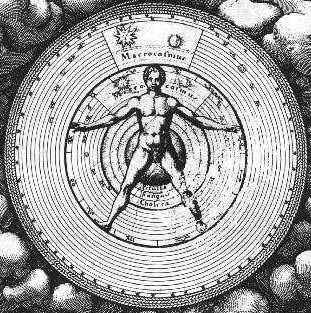

Sophisticated Naïveté

When I try to think of the philosophical underpinnings of Scheler’s thought, I am led to the phrase “sophisticated naivité.” His writings may be full of complex arguments and ideas, but his outlook is deceptively simple. He thinks the world is ordered according to a logos and that man is the microcosm, the prince of creation. Like I said, there are many, many arguments for this—some of which are phenomenological, others grounded in the history of ideas—but at base, one gets the impression that Scheler just has faith in himself and in his ability to perceive these things accurately.

His works are not the scrawlings on the cell wall of a man imprisoned by abstractions, but the fruit of a mind that has been watered with wonder and reverence for all creation, which as Aristotle wrote, is the true source of all philosophy.

In ethics, he has some very sophisticated critiques of Kant (and everyone else), but all this baroque theorizing terminates in a place that is remarkably similar to what philosophically ignorant people intuitively believe. In fact, Scheler tells us that his view can be referred to both by the low-brow name, “emotional intuitionism,” and the high-brow one, “non-formal apriorism.”

This brings us to the topic of essence. His friend, the Spanish philosopher Ortega y Gasset, described Scheler as being “essence intoxicated.”7 It is often said that Scheler uses an “intuitive method,” but this is really just to say that he believes that intuition (anschaunng) can furnish us with real knowledge. This is especially difficult for people in our century to understand because most of what is written in philosophy and science today is based on conceptual thinking, with intuitions merely being a kind of gut-feeling rather than a sui generis mode of perception.

Put simply: Scheler thinks he can “see” (through intuition) the essential make-up of the world, and that such intellectual visions are objective; moreover, everyone can see them, since all beings co-exist within the same essential matrix.8

This is perhaps the most difficult part of Scheler’s view, as it requires something beyond any clear exposition one can lay down in print: a comprehension of intuition and of essences (wesensschau).9 Sadly, a full treatment of that is not possible here, since a topic like intuition is a very thorny bramble indeed. I will, however, give some simple examples that demonstrate this style of thinking.

A platonic question such as “what is justice?” is met with a simple answer: justice is an essence, a value property. There is no breaking down the idea of justice into a conceptual scheme or defining it in a rigorous analytical way. It’s a metaphysical primitive. The world has these properties, and we can see them—or fail to see them.10

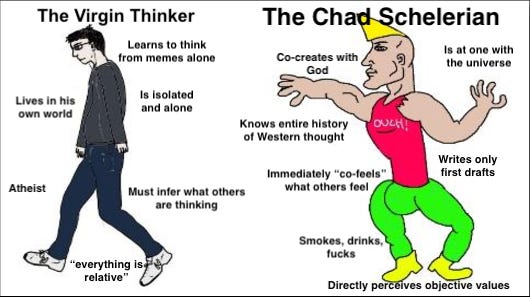

There is a total lack of neuroticism in this way of thinking, an absence of all hyper-sophisticated abstractions. You either see things clearly or you don’t—and if you don’t, well, too bad for you. Very chad.

This leads to some very simple and ostensibly naive solutions to enduring philosophical problems. For example, the final section of Scheler’s first book, The Nature of Sympathy, explores the problem of intersubjectivity and our awareness of other minds. He thinks we simply see other people; we have direct awareness of them. Any kind of solipsistic, Cartesian worries never arise. He is almost like the anti-Wittgenstein in this respect: the limits of his language are just a small part of his world.

One can disagree with this kind of thinking—and what I have written here is by no means an adequate presentation of the view—but you get the idea. And if you take this to its logical conclusion, as Scheler does, we end up with a radically different picture of the universe and man’s place within it.

The Solipsistic Virgin vs. Microcosmic Chad

The default view today, which is held implicitly (and perhaps unconsciously) by much of the Western world, is that we are all locked in our own minds. The soup of electrical charges engenders consciousness somehow, which is then modified through sense-perceptions. We go about trying to interact with each other every day. Always unsure about whether we can actually make contact, always using words which may or may not be adequately understood. Our feelings are merely subjective, bound by evolutionary pressures and social conventions; the world is without meaning; et cetera.

Man is atomized. And even if one believes in a transcendent God, he often remains so.

The Schelerian view, which at base is an update of the much older Aristotelian tradition,11 holds that we are much more interconnected than that. He thinks that when we see that Marie is sad, we see her sadness. We do not “infer” from her facial expressions that she is sad: we directly perceive her mental state. Mind may be conditioned by sense-data in complicated ways, but it is fundamentally directly in contact with the world at large. And the world is larger than most people think. In addition to physical phenomena, it is also replete with value properties which can only be accessed through intuition and affective perception—things like beauty and justice, aspects of the world which, for Scheler, are every bit as objective as colour and shape.

Even if the human animal may be a “monkey on a rock in space,” the human being is conceived of as something immeasurably greater. For Scheler, the spiritual personality is able to directly interface with the essential structure of the world, with other such beings, and with the ultimate ground of reality itself in a genuine, immediate, pre-conceptual way. As the mirror of the universe and co-creator of God, the Schelerian man moves forward with a kind of metaphysical dignity: being at once a part of everything and still himself.12

And if you disagree, he couldn’t care less. He’s serene.

This is a good point to end on because Scheler wrote more clearly about the emotion of “serenity” than anyone in history (so far as I can tell). According to him, the emotional life has levels; it’s stratified. You can feel pain and be happy. You can feel healthy and be sad. These feelings reside on different emotional levels, and at the most basic level, the deepest and most important, lies the seat of serenity.13

The difference with this emotion is that, unlike more common emotions like peacefulness, happiness or sadness, it is not presented as belonging “to me.” Serenity does not pertain to the ego but rather pervades one’s entire world, remaining stable throughout the fluctuations on the more superficial levels of consciousness. Thus, “A serene face remains serene, even while crying.” (Formalism, 331)

Scheler may have lived a chaotic life, a life of highs and lows, of great successes and abysmal failures; but in reading him, I have the impression that he was always serene, that at base he always felt a sense of wholeness and wonder emanating from within the world. Such a feeling, if you’re lucky enough to have it, persists through all the tribulations of one’s life, through happy times and sad times, through sickness and through health, for it lies beneath them all. It rests like a light behind the world, suffusing the entirety of the spectacle with a steady, wholesome, calming glow.

If there is an “essence” of what it means to be “chad,” then it seems to me that this is definitely a part of it—and that Scheler can rightly be considered “the chad philosopher.”

Yes, his first name was really Maximus, though all the books simply say “Max.”

I knew a guy who told me he had lived in the same building as Scheler, and that Scheler was known to have brought prostitutes back to this place. Can’t verify this, but it’s funny.

The French Philosopher Alexander Koyre writes that Scheler’s brilliance was one of the high-points of his education: “About Scheler’s group, let us say then, that the contagion of his thought, perpetually in action, intoxicated us with a fertile and lucid intoxication which raised us above ourselves and made us capable of participating in this agility of seeing and even of finding ourselves things that we would never have been able to discover without him.” ‘Max Scheler’, Revue Allemagne, X (August 1928), p. 98 (my translation)

For those interested in learning more about his life, I would suggest the book, Max Scheler: an Intellectual Portrait by John Staude. It paints an interesting picture of this fascinating, if flawed, man.

He actually acknowledges this diversity in the preface to his first book, On the Overthrow of Values: “The isolated form in which every problem appears posed here means only this: that all systematic unity and all architectonics of thought must spring anew from the depths of each subject area treated, and thus must not be imposed constructively from above on any one area. The true unity of thought, world, and personality of a writer is measured by this hovering ideal.” (my translation) This is a representative quote and suggests that, rather than a conceptual system, his unity is grounded in something more fundamental.

This seems to have been a trend during that time, and it is pretty common to find similar habits in writers like Nicolai Hartmann and Ernst Cassirer—two neglected giants who I may write about in the future. It seems that a hundred years ago philosophy was an activity for the bros. There was an elevated class of European intellectuals—real intellectuals—who basically wrote for each other. Today we are told to cite everything unless it is supremely obvious; they seem to have held that almost everything was supremely obvious. This makes for an intimidating reading experience for those of us, like myself, who are not so well-educated. It’s very humbling to actually see how much further ahead those guys were.

The same could be said for many of the early phenomenologists (Husserl, Pfander, Reinach, Stein, Ingarden…).

This is not, however, the same as a classical Aristotelian view, and Scheler has read his Nietzsche. He calls his position “a perspectivism governed by essential laws.” (Problems of a Sociology of Knowledge) It’s a way of both keeping an objective world while taking into account each person’s relative perspective. No idea why this isn’t a mainstream position.

It is worth noting that for Aristotle, the grandfather of essentialism, essence and concept ran closely together, so that essence often took the form of a definition. “Man is a rational animal,” for example. This is not the case with the early phenomenologists.

I should also note that such a view is sometimes even attributed to Plato. In many dialogues, for example, one can read Socrates as showing that our understanding of certain virtues (values) can’t be exhausted by the discursive intellect. This is a contentious point, however. I should also note that this emphasis on “seeing” is partly why Scheler (and the rest of the early phenomenologists) has no direct philosophical descendents and is not popular today outside of a few academic strongholds. Academics don’t like this kind of “either you see it or you don’t” philosophizing.

See David Charles’ The Undivided Self for more on this as it pertains to Aristotle.

Weininger, despite my characterization as the “incel philosopher”, has similar chad-like metaphysical views.

See §10 of my essay Absurdism is False for more on this.

this was rly well written im a fan

are philosophers just veiled priests? preaching the current religion of no nation, no family and no god?